After finishing my full-time work at the Frischknecht Lab, I continued my medical career. The last year of German medical studies consists of an internship, which I had the privilege to spend partly in Kigali, Rwanda. This is a short report on these 4 beautiful months:

First, let me give you a few facts: Rwanda is a landlocked country in Eastern Central Africa bordering Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Burundi. The size is only 1/14th of Germany. With a population of about 12 million it is the most densely populated country in all of Africa.

Some call Rwanda the "land of a thousand hills" and to be honest, to me, especially in the countryside, that's exactly what it is - steep hills with the lushest green of equatorial jungle, fields and houses wherever you look. Kigali, the country's capital, is the modern epicentre of Rwandan economic growth in past years, sporting a downtown, international congress halls, restaurants and pubs and a vibrant art and music scene. Also, it was the place I decided to stay at.

Unfortunately, one cannot give an introduction to Rwanda without mentioning the darkest part of Rwandan history which only took place about 25 years ago: the genocide against the Tutsi, the horrible ethnic killing of 10% of the population that destroyed families and dreams.

However, circumstances have changed dramatically in recent years and even though the acts of murder are still deeply present in the people's daily thoughts, Rwanda is now considered one of the most stable and well-governed countries in Africa. Talking to people they often mention proudly the excellent security, economic growth and cleanliness and that Rwanda wants to be middle-income country by 2035 and a high-income one by 2050. Foreign press sometimes calls it the "Switzerland of Africa". Perhaps progress sometimes comes at the cost of personal freedom and it shouldn't be seen in that one-sided way. Still, I have never before visited a country where the spirit of change and economic growth coupled with national pride was so present. But I am getting ahead of myself here...

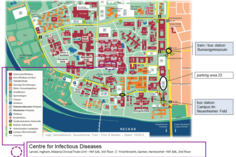

I arrived in the land of a thousand hills in September 2022. Our shared house had a stunning view of the surrounding valleys, was at the edge of Kigali downtown and in walking distance to the hospital called CHUK. CHUK is the country's biggest hospital and teaching hospital of the University of Rwanda with a capacity of more than 500 beds and an even greater number of outbound patients. As a public hospital in a country with an (almost) universal healthcare system it is an important healthcare provider, not only for the capital.

During my internship I mainly rotated in the surgical wards which include General, Acute, Pediatric, Neuro, Orthopedics, ENT and Plastics.

Rwandan medical school is structured similarly to the German one. The last year also includes an internship in different departments. Handling my own patients, assisting in the theatre or having night duties: I could rotate together with the local students and had likeminded company (and sometimes help translating Kinyarwanda) in all these activities and felt like a part of the team. Also, education, even though hierarchically organised, is excellent and possibly more hands-on and patient-centered with a lot of bedside teaching.

In ideal situations, especially in the private clinics of the capital, medical standards don't really differ from the ones in Germany. Most blood tests, an MRI scanner and even a fancy microscope for neurosurgery were available. Rwandan citizens usually have health insurance covering at least 80% of treatment costs. The reality in a public hospital like CHUK meant, unfortunately, that the remaining 20% were often still too much for the patients to pay. Also, due to import taxes (which, in theory, should strengthen the local economy), and Rwanda's landlocked position, certain medical consumables are incredibly expensive. As a consequence, routine blood work would not be done, certain examinations not performed, or subpar operational techniques had to be chosen. Coupling this with a long initial journey to reach CHUK, a possibly critical nutritional status and bedside care done by the patient's family rather than trained personnel, the rate of infections was high and hence the outcome for most of the patients, especially in critical situations, was poor.

The most common diagnoses obviously depended on the department, still, some of them are way more common than in Germany. In acute surgery, I encountered a lot of typhoid fever and the underlying complications as well as different kinds of abdominal trauma. The orthopedic ward was packed with people having had road traffic accidents, mainly on motorbikes, the most common means of (public) transport to tackle the Rwandan hills (at least helmets are mandatory...).

One of the things I had not imagined seeing so often where newborns with gastroschisis (basically a gap in the abdominal wall). At a rate of 2/10,000 children gastroschisis is surprisingly common. In Germany these cases are mostly diagnosed in utero, then born in specialised hospitals, where the gap is closed directly. If necessary a ventilator is used in the first weeks to assure sufficient ventilation despite the increased pulmonary pressure after closure.

In Rwanda, however, the children are mostly diagnosed after birth and are only then brought to CHUK, the only hospital able to deal with these birth defects, from all over Rwanda. At least one newborn is admitted every week. The hospital owns 3 ventilators suitable for children. This makes primary closure very difficult as there are just not enough ventilators for all young patients. The pediatric surgeons at CHUK instead use so-called silo bags to contain the bowels and perform reduction over a period of a week or more without ventilation compromising pressures. The delay, however, results in vastly more infections and other complications. While around 4% of newborn children in high-income countries die with gastroschisis or its complications, 70% or more do so in Rwanda, for a great part due to the "simple" lack of ventilators.

I think, however, CHUK is receiving the "worst" patients from the hospitals in Rwanda, simply because they are the only ones able to treat them. Hence my picture could be a bit askew. The great work with possibly limited resources of the doctors and nurses in treating patients, but also teaching students shouldn't be underestimated and makes a huge difference.

During the 4 months I had plenty of time to admire Rwanda's natural beauty: The beaches at lake Kivu, Volcanos National Park, home to the famous mountain gorilla, I went on safari etc.. I even had time to visit neighbouring Burundi with some friends, which despite its beauty still made us appreciate Rwanda's undeniable success.

I am grateful to have had the chance to visit. I not only learnt and experienced a lot but also made many good friends and future colleagues along the way.

A quick malaria side story to finish: In the last weeks of my stay I developed intermittent subfebrile temperatures. Despite Kigali's altitude of about 1,600m malaria is still very common. Even though having taken prophylaxis every single day, I decided to do a rapid test, which became positive immediately. Shocked and also a bit worried by the probable need for treatment right before Christmas, I consulted the emergency department of the local university hospital. Upon arrival they decided to isolate me - apparently, malaria is contagious ;)

In the end, everything went out fine, smears and other blood work were done, and I was thoroughly examined. Surprisingly, nothing could be found but since the fevers have not returned, I decided to let the matter rest. Whether it was an invalid test or maybe even due to the occasional bite in the lab, I think I will never know.